In the first episode of Girls, Lena Dunham’s Hannah Horvath submits herself to awkward, humiliating and—for some—realistic sex. Her friend with benefits, Adam (Adam Driver), takes charge of the encounter and won’t even answer the question of whether he’s putting on a condom. It was a scene that made many cringe, but it signaled a transformation in the television landscape. Sex on TV, it turned out, didn’t have to be romantic—or even appealing.

Five years after Dunham’s first unsatisfying hookup on Girls, sex on even the most mainstream shows is beginning to look more like what happens in our own bedrooms, from Marnie receiving anilingus on the season premiere of Girls to The Americans’ infamous 69 scene last season. We’ve entered a new era of realistic, wide-ranging on-screen intimacy that reveals as much about our society’s evolving social and sexual politics as it does about any one character.

Some of this is a result of technological changes. New streaming services, not bound by industry rules and norms, are taking bigger risks, such as the Amazon show Transparent about a middle-aged father coming out as transgender. And the growing number of platforms is making room for a more diverse array of writers on shows like Girls, Transparent and How to Get Away With Murder. This new generation of dramatists is disposing of the straight, often white male point of view and approaching sex from the female, gay or trans perspective. House of Cards’ Beau Willimon even credits the advent of the Internet and its abundance of online porn for freeing him from relying on sex scenes as an enticing ratings booster.

Critics debate whether we’ve passed the golden age of television defined by shows like The Sopranos and The Wire and whether new TV dramas will live up to those classics. One thing is certain though: We are in a new age of sex on TV. TIME spoke to six of the showrunners who are taking sex seriously.

![]()

Whether it’s two female prisoners competing to see who can coax the most orgasms out of their fellow inmates in Netflix’s Orange Is the New Black or a good, old-fashioned kiss-and-cut-away on ABC’s Scandal—the way intimacy is shown on the small screen has come a long way since 1952 when CBS forbade Lucille Ball from calling herself “pregnant” on national TV, substituting instead the priest-approved word “expecting.”

The evolution of sex on TV moved slowly for the next six decades. Samantha and Darrin shared a bed on Bewitched in the mid-1960s—a step forward from Lucy and Desi Arnaz’s twin beds on I Love Lucy. The titular character on Maude decided to go through with an abortion in 1972. Billy Crystal played the first openly gay character on Soap in 1977. ABC won a battle against the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), a government agency that regulates indecency in public media, over a steamy 2003 NYPD Blue sex scene that showed bare behind.

But by the early 2000s, faster Internet speeds became increasingly common and with them easily accessible pornography. No longer did kids have to visit a friend with an HBO subscription to see nudity. Access to graphic sex online spurred networks into what became a nudity arms race. A 2005 Kaiser Family Foundation study found that the number of sex scenes on TV had doubled in the last seven years and that 70% of all shows on TV included some sort of sexual content. This was especially true of popular shows among teens like The O.C. and Gossip Girl, whose vibrant plotlines included underage orgies and teens bedding their friends’ parents.

FCC rules have always been extremely vague. According to the group, genitals and nipples are not allowed on network or cable (versus premium channels like Cinemax or HBO), but what characters can say or reference is more of a gray area. Obscene material that could result in a fine must have “prurient interests” lacking “literary, artistic, political or scientific merit” as defined by “the average person.” Premium channels tried to lure viewers from network TV and basic cable with nudity. Writers working for HBO, Netflix and Amazon say they only have to convince their bosses that certain scenes are not “gratuitous.”

But while porn may have hastened the arrival of graphic sex on TV, it also presented a problem to directors.

“It’s difficult to film sex scenes not just because it’s awkward for the actors to be disrobed making out with a colleague in front of a lot of people, but mostly because it’s very difficult to make it look real,” says Beau Willimon, the showrunner of House of Cards, the award-winning Netflix series about devious politicians. “You run the risk of pulling the audience out because they’re reminded in that moment that they’re watching a show, and usually you are trying to avoid that.”

In many ways, porn has been freeing to TV writers. “I think there was a pressure for a time for shows and movies to provide that service, and it always felt false because it was like, ‘Here’s the titillating part of the movie.’ It was a marketing technique,” says Willimon. “Now you can’t put anything on TV that’s more pornographic than what’s easily available with a few mouse clicks. So you can really focus once again on character, and those characters can engage in sex the way actual humans do.”

Not only have Willimon and other writers made sex essential, but they also have used it to start a conversation about sexual identity, feminism or even our moral fiber.

![]()

The state of a couple’s sex life can say a lot about their relationship. And even the most innocent sitcoms will offer viewers a glimpse into the characters’ love lives with familiar tropes—the kids walking in; the attempt to not be a “boring couple” with sexual misadventures; the makeup sex after a fight.

But many new shows use the bedroom as an integral storytelling vehicle rather than a cheap trick to spice up the plot. The politicking on House of Cards, for instance, leaks into the bedroom. Willimon says of political power couple Frank (Kevin Spacey) and Claire Underwood (Robin Wright): “They are not ordinary, so their sex lives aren’t ordinary either.” Some examples of this extraordinary sex include Claire masturbating a dying man, Frank performing oral sex on reporter Zoe Barnes (Kate Mara) while she talks on the phone with her father and Claire and Frank engaging in a threesome with their bodyguard.

But the married-couple sex scene most widely praised by critics in the last several years was one between Elizabeth (Keri Russell) and Philip (Matthew Rhys) Jennings, Russian spies masquerading as American suburbanites on FX’s The Americans.

Showrunners Joel Fields and Joe Weisberg began season two sitting in their writers’ room trying to list every single sex position known to man. They had decided that in the first episode, Elizabeth and Philip needed to reconnect after Elizabeth’s absence at the end of last season. They wanted to restore an equal power balance in the relationship. “We were looking for something that expressed mutuality but also great intimacy,” says Weisberg.

To add an extra complication, they wanted the couple’s daughter, Paige (Holly Taylor), to walk in on them as she was trying to snoop for clues about her parents’ secrets. This would have long term consequences on the show as Elizabeth and Philip struggle to establish trust with their daughter while hiding their identities. “This scene of a kid walking in on the parents is a cliché,” Weisberg says. “How can we make that original?”

They settled on the only position they thought was mutually pleasurable and vulnerable: the 69. If showing a man give a woman oral pleasure is rare, the 69 is the unicorn of TV sex. The first question the director of the episode, Thomas Schlamme, asked was how they would position the actors. “You’ll notice that the choice we landed on didn’t involve dominance,” Fields says. “Philip wasn’t on top, and Elizabeth wasn’t on top. That was a specific choice.”

After it aired, Vulture called the scene “TV’s most emotionally resonant 69 scene ever.” TIME’s James Poniewozik pointed out that the position “emphasized how sexually egalitarian the show is.” The 69 was simultaneously an act of feminism and realism. In a drama where two spies set “honey traps” for a living, such relatable moments of intimacy are what have kept it grounded.

It’s a lesson Fields and Weisberg learned after a few mistakes. “There was a scene with a prostitute in season one that ultimately, when we look back on it, we cringe and feel like that really wasn’t about the character. It was about boobs. It wasn’t central to the story, and we’d never do that again,” Fields says. “I guess that’s part of the learning experience.”

![]()

If The Americans explores the intimate complications of sex between two (mostly) committed people, Girls tries to take the same realistic approach to the confusing hookups of 20-somethings.

“When one scene would end, we would go 10 more minutes into that scene and follow people into the bathrooms. In sex scenes, we don’t cut away after the kiss,” says Jenni Konner, who runs the show with star Lena Dunham. “We work really hard not to do the glamorous version of sex. This feels more honest.”

That means people of all shapes and sizes having both good and bad sex. It means the flaky Jessa (Jemima Kirke) skipping out on her abortion appointment to hook up with a stranger in a bar bathroom. It means Hannah buying spider-web-like-lingerie to try to fix her relationship. It means two people realizing they are sexually incompatible when one person cannot or does not pleasure the other. It means interruptions, complications and awkward conversations that inevitably arise in real life.

These plot lines often carry feminist undertones—after all, Dunham is one of the few young women who have been given the chance to make her own TV show. The mere fact that the Girls writers’ room has a strong female representation gives the show a different tenor. “We’re feminists, and that’s important to us,” says Konner. “I don’t think the show is message-y, but by default, it becomes political because we tell stories—like the abortion storylines—that happen to real people we know in real life.”

But while the writers and stars of Girls have become used to fielding questions about the intent behind each nude shot, How to Get Away With Murder showrunner Pete Nowalk was taken by surprise when publications like BuzzFeed and the New York Times began commenting on the gay character Connor’s active sex life. “I don’t even know how to talk about it because it’s not ever been a conscious part of our writing process,” Nowalk says.

The sex on the show isn’t “shocking” in the way the sex on Girls is. As Nowalk points out, Showtime’s Queer as Folk (based on a BBC show of the same name) aired much more scandalous scenes between gay characters on TV in the early 2000s than How to Get Away With Murder does now. But Connor uses a Grindr-like app to find men, and one hook up even says, “He did this thing to my ass that made my eyes water”—a sentence likely never uttered on American network TV before.

“I’m a gay man living in Los Angeles who has gay friends,” Nowalk says. “So putting an app like Grindr on the show is not out of the ordinary to me. It’s just reflecting what it’s really like to be a 20-something gay man.”

In fact, he worries that so much attention on Connor will only serve to trivialize him. “I guess I have just been surprised that people have taken notice of it as something new,” says Nowalk. “I don’t want people marginalizing the character based on the fact that Connor is having sex with men. Viola Davis’ character, Annalise, is just as sexual as Connor, but she doesn’t get as much attention in the media. I just want people to pay attention to the character as much as they do to his sex life.”

That is the challenge of expanding the TV universe. Audiences have seen so many straight, white men on their screens—good guys, bad guys, geniuses, idiots—that they don’t think the choices of any one character reflect upon the entire straight, white male community. Not so for minority characters who, by virtue of being historically ignored by mainstream television, come under much greater scrutiny. Writing complex gay, female, trans or minority characters becomes a challenge: perpetuating stereotypes can be dull and offensive, and straying too far from them can alienate big audiences and the network executives who seek them out.

![]()

Large media companies are at their core risk-averse and therefore slow to change. That’s why critics so quickly embraced Jill Soloway’s daring Transparent, an Amazon-produced show loosely based on her experiences when her father came out as a transgender woman. But before Soloway thought up Transparent, she was a writer on HBO’s Six Feet Under, which aired from 2001 to 2005. It was there that she realized very few female characters on TV could be sexually liberated without being judged or punished by the show.

“I realized that it was a feminist act simply to allow Brenda to meet Nate and have sex with him in an airport and still be an okay person,” she says of two of the lead characters on Six Feet Under, played by Rachel Griffiths and Peter Krause.

This may not seem revolutionary, but Soloway says that Brenda was a feminist hero for not falling into the two categories writers often place women: the Madonna and the whore, the wife and the mistress, the virgin and the slut. “A patriarchal society divides women into either and reduces their power by not allowing women to connect with their own sexuality. In most stories, women are punished for being sexual,” she says. Think: the sexy girl that’s killed first in horror films, the friend who is ostracized for sleeping with someone else’s crush, the murdered prostitute.

When men are producing, directing and writing, she argues, they produce material that makes them feel safe. That’s why we see so many frumpy guys with beautiful wives on TV. “I don’t think that most men know this, but a lot of the stuff they create is propaganda for the way they want to move through the world. It’s the definition of male privilege, and it influences the way real girls act as they watch this stuff growing up.”

This reductive view of women is reinforced by camerawork and something that cultural critics call “the male gaze.” A traditional sex scene will take the male perspective and focus more on the woman than the man. The camera will settle on the glossy-lipped lady as she arches her back and does her best Victoria’s Secret ad impression. It’s what men see—or what they want to see—during sex, not what women actually experience.

Soloway wants to wrest control of the dominant narrative from men. And that doesn’t just mean “woman on top.” It means making women vulnerable and allowing them to make choices without judgment.

“By the time I started filming Transparent, I wanted to show women being in their bodies and experiencing the complicated, messy reality of being human,” says Soloway. In an early episode, Gaby Hoffmann’s Ali attempts a threesome, and the camera follows her eyesight. “In the editing room, I worked really hard to try and stay in her point of view and never use the objective camera, which would not only be looking at her in this scenario but inviting the audience to judge her.”

This active attempt to extend beyond the male gaze has led to some complicated questions. While the appearance of women’s breasts, bottoms and even pubic area are routinely distributed on television, in magazines and in porn, nobody seems to have figured out what parts of the male body people want to see.

“What is the female gaze? If women are looking at a naked man, what is a turn-on for them? Do people want to see male full-frontal nudity on TV? Is a man without an erection too vulnerable to show? Can you even show an aroused male body? Is that porn?” asks Soloway, who hopes to tackle male full-frontal nudity in season two.

And she’s not alone. Jay Duplass, who stars on Transparent, also co-writes HBO’s new marriage dramedy Togetherness with his brother, Mark. (Mark Duplass acts on Togetherness, occasionally in the buff.) The Duplass brothers recently told Seth Meyers on Late Night that they have a rule on their show called “balls equality”:

“For every boob that shows up, there should be a testicle to go with it.”

![]()

HBO has long tried to maintain a reputation for taking risks with sex and nudity—and has occasionally come under fire for doing so. Take, for instance, an episode in the second season of Girls when the writers explored the blurred lines of consent.

As early as the pilot, Girls fans knew that Adam had particular interests in the bedroom. But that didn’t stop an outcry over a scene in which, after drinking, he demands that his then-girlfriend Natalia (Shiri Appleby) crawl on her knees to the bedroom before he pulls her off the floor, has sex with her from behind and finishes by masturbating on her chest. Some called the scene forceful and awkward. Others labeled it rape.

“I knew that that scene was ambiguous and played with ideas of consent, but I never, ever thought it would be interpreted as rape,” Konner says. She points out that Appleby’s character never says, “No.”

But, critics argued at the time her consent seems half-hearted at best. And when Adam begins to masturbate on her, she says, “No, no, no, no, not on my dress!” and later concludes, “I really don’t like that.” Some detractors reasoned that calling the scene ambiguous excused Adam’s aggressive behavior. Had Adam stopped to listen, he would have known she was unhappy.

And yet that situation is familiar to both those who misread signals from their partner and those confounded by when and how consent must be given. It fueled the online debate about what qualifies as consent, especially when alcohol is involved.

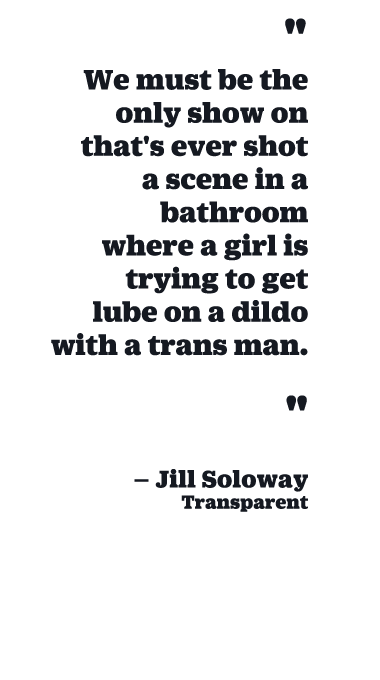

Transparent, which starts its second season on Amazon sometime this year, broke new ground in a different way, showing something that few people have experienced, let alone seen on TV. Midway through the first season, Ali goes on a date with a trans man named Dale (Ian Harvie). At one point, they sneak away to a public bathroom with a recently-purchased sex toy. Things get uncomfortable as the two try to pry the box open and navigate the mechanics of the act. Eventually, Dale drops the dildo on the bathroom floor, killing the mood.

The scene could have easily been structured as a lecture—this is how a transgender man might have sex—which Soloway says she intentionally avoided.

“At one point, we were shooting, and we realized we must be the only show that’s ever shot a scene in a bathroom where a girl is trying to get lube on a dildo with a trans man while her trans parent is on stage singing outside,” she says. “But, to us, that’s a comedic moment, and any time we can throw something into a comedic setting, it takes away from it being too preachy.”

![]()

The acclaim for Transparent—let alone its very existence—speaks to how quickly perceptions of transgender people are changing in America. The show and its leading actor, Jeffrey Tambor, won Golden Globes for its freshman season, and in the months since, transgender issues have come to the fore.

The media are looking to Soloway as they report on Bruce Jenner, the former Olympian and reality celeb who is transitioning to a woman. After Soloway dedicated her Golden Globe to Leelah Alcorn, a trans teen who committed suicide after her parents forced her to go to conversion therapy, the White House also cited Leelah as their inspiration for endorsing efforts to ban such therapy practices for gay and transgender youth. And when the show took on the debate over bathroom access for transgender people, politicians began to take sides on the issue.

The transgender movement may have helped Transparent make it to air, but the show has also educated people about the fight for transgender rights.

This symbiotic relationship between television and social movements is nothing new: The same-sex marriage movement has gained momentum since gay couple Mitch and Cam (Jesse Tyler Ferguson and Eric Stonestreet) first appeared on Modern Family in 2009. Fans of Girls, including Taylor Swift, have credited Lena Dunham with teaching them about feminism. The more familiar and commonplace feminist and LGBT issues are in the bedrooms on TV, the quicker public perceptions change in the privacy of people’s homes.

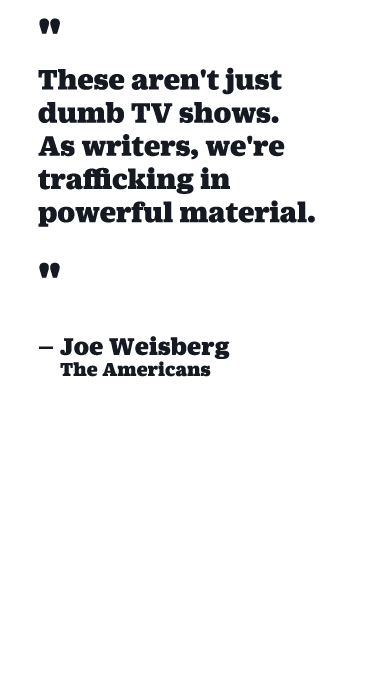

Joe Weisberg and Joel Fields of The Americans realized the impact of their program this season. In the first episode, a woman is choked to death during sex. It’s a brutal scene, but at a screening of the episode, a few men began to laugh. When the viewing was over, several audience members took it upon themselves to admonish those who made of light of the woman’s death.

“I just thought it was a really interesting reminder to us as the writers of what powerful material we’re trafficking in,” says Weisberg. “People watch this and have reactions to it. And maybe some of the people who watch it aren’t mature enough for it. Maybe somebody standing up and telling them why it wasn’t okay to laugh taught them something.”

People look to popular culture to dictate what’s cool, what’s acceptable and what is not. These showrunners may have as much influence as politicians to change the tide of public opinion on social issues, and perhaps more.

“The point is these aren’t just dumb TV shows,” says Fields. “It means something to people.”